Read the opening chapter of welcome To Glorious tuga by Francesca Segal, a Reader Favourite in our Good Books Summer Collection.

Islands are places you flee to, or places from which you flee. For days the ship had been anchored, waiting for the seas to calm. They were a mile off the reef- wrapped coast of Tuga de Oro, a tiny British overseas territory, the world’s most remote inhabited island, on which life was variously described as ‘turning the clock back a hundred years’ (Lonely Planet), ‘an English community life from a bygone golden era’ (Time Out), ‘a modest British seaside hamlet airlifted to the Tropics’ (Fodor’s Travel Guide) or, less warmly, ‘stuck in the fifties, just possibly the eighteen- fifties’ (The Wanderer). Certainly the weeks of this ocean voyage had felt positively Victorian.

They were nearing Tuga, but Charlotte Walker had so far seen nothing of her future home except roiling ocean through her cabin’s filmy porthole. A few days out of England she had hoped some fresh air might quell the rising nausea and had opened this window, but instead had almost asphyxiated herself with a warm cloud of diesel fumes from the engines, and would not make that mistake again. Now, finally, the lighters would call in the morning and with them salvation, at least from seasickness. Soon she would be in the dense beauty of a pristine jungle, with her tortoises.

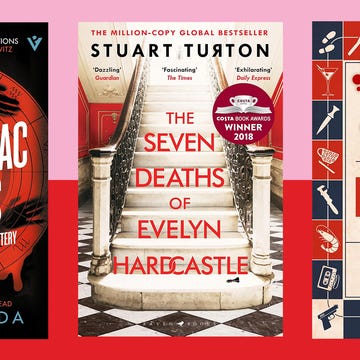

What to read next

Charlotte was twenty-nine, and held a PhD conducted at the Institute of Zoology in Regent’s Park, investigating the impact of non-native newts on the UK amphibian populations. She had always loved amphibians and reptiles, particularly tortoises. They were easy metaphors for resilience and independence, and as a sensitive child, a homebody, and the daughter of a commanding and intrusive single mother, she had envied their ability to retreat into a physical space that literally no one else might enter. This affinity was disapproved of by Lucinda Compton-Neville, herself a sociable and highly sought QC, who considered her only child’s achievements to be assets of her own, and found no social cachet in slimy things.

Charlotte’s early childhood had been overseen by nannies, and populated with small creatures the housekeeper resented; gerbils and hamsters and funfair goldfish, and at one stage a bearded dragon she lovingly named Joan, after Joan Beauchamp Procter, the first female curator of reptiles at London Zoo. Lucinda detested this animal in particular and refused to speak its name, while slug-hunting for the bearded dragon had pushed the nanny to the edge of resignation. Only pity for her preternaturally well-behaved charge had kept her in the job.

When Charlotte was ten, Lucinda had married a fellow barrister, Adrian Walker, and had ruthlessly dispatched the creatures that had till then been Charlotte’s solace, reasoning that a spirited trio of much smaller stepbrothers would be menagerie enough. Charlotte’s prep school got the hamsters, a terrarium of dart frogs rode grandly back to Palmer’s Pet Shop in a black cab, and the stick insects were set loose to try their luck on the box hedges of the Inner Circle. Charlotte Compton-Neville was reborn as Charlotte Walker. At night she sobbed, quietly, unobtrusively, for these lost companions. Still, she had offered up her small heart to Adrian Walker, full of hope that here, finally, had come a father, and a reward for all the years of unspoken longing. But the step-siblings rarely visited, and the underwhelming and unresponsive stepfather was divorced within the year, reappearing in their lives intermittently and only as Lucinda’s opposing counsel, periods during which her mother’s mood would be dangerous and erratic. Lucinda became Compton-Neville again. Charlotte, by then at secondary school and wise to the semiotics of a double-barrel, would not relinquish Walker.

She did not wish to be remarkable, in any direction. From then on the animals in Charlotte’s life had been mostly imaginary or theoretical, until college. As an undergraduate, Charlotte was made anxious by the distance between herself and her fellow veterinary students.

The others studied together and drank together and exercised together and slept with one another in various configurations, and Charlotte would join them in the library, and usually slipped away from the pub after the second round. She wanted to fi t in, but not enough to do the things they did. She suffered real fear of silliness, of social risk, of emotional exposure. She could not pretend to enjoy rappelling in Wales, nor racing up peaks in the Lake District, nor downing pints on a Bloomsbury pub crawl in animal fancy dress. She had never downed a pint, nor smoked a cigarette, nor had a one- night stand, and had she done any of these things it would only have been to disguise herself as someone whose natural behaviour it was, a pretence that would have fooled no one. It did not help, of course, that most of the students at the RVC came from outside London and lived together in halls, bonded by the constraints of student loans, while she still lived in alienating privilege and splendour in a white stucco Nash house in the park, so grand that she was ashamed to ask anyone home.

On graduation, most of these contemporaries joined small-animal practices or took advisory roles in farm-animal husbandry, while Charlotte sank with gratitude and pleasure into a PhD based in a multidisciplinary lab at ZSL, and a life with the newts. Newts were plentiful in England. She felt at home with the team of academics, biologists and bioinformaticians, recognising herself in their introversion and rigour. Academic herpetologists in particular were usually an obsessional lot – patient, dogged and retiring; playful, but on their own terms. Not unlike tortoises.

‘Knock, knock.’ The door opened a fraction and Charlotte quickly smoothed down her covers and combed through her tangled hair with her fi ngers. Dan Zekri appeared, bearing a small stainless- steel tray on which stood a mug of soup sealed with cling film, and a brown roll. He had dark skin, very blue eyes and deep, unexpected dimples, a striking combination that Charlotte did not yet know was characteristically Tugan. Charlotte herself had dimples, and felt both kinship and competition with the rare others whose dimples were exceptional. Dan was not tall but solid, square as a rugby player and courteous as a footman, and was so gleaming and healthy that her squalid state had at fi rst made her want to curl up with shame. Then the seasickness had taken a turn for the worse and she ceased caring if she lived, let alone how handsome was the man who held her hair back as she retched. Dan came each day in an apparently unending supply of clean white shirts, smelling of menthol and sea air, and in her cabin Charlotte sweated and festered and was sick.

She longed for a breeze. Dan arrived with a portable fan. ‘How’s my patient?’

Charlotte sat up in her bunk with trepidation. She waited, but the impulse to vomit did not come. The room rocked, but did not spin.

‘Better, maybe?’

‘Good news. Last tinned broth, I promise; I happen to know there are carrots and onions in cargo. Once we land you’ll have more chicken soup than you know what to do with.’ Dan handed her the mug and then sat in his traditional place, on the fl oor of the cabin by her feet. He leaned easily against her bunk and picked up a slim journal.

‘Right, where were we. Keep drinking, please. We’d just finished “Genetic differentiation over a small spatial scale in the smooth newt”. Next is “Supplementary Materials for ‘Genetic diff erentiation over a small spatial scale in the smooth newt’ ”.’

He threw his head back to regard her. ‘I presume you don’t want the supplementary materials? Too much of a good thing, maybe.’

Charlotte could not answer truthfully, for one did not look in the mouth any gift horse willing to read aloud from the British Journal of Herpetology. Dan regarded her steadily.

‘I just want to know what’s in them,’ she admitted. ‘A table of the latitude and longitude of each surveyed pond. The most potent narcotic yet discovered.’

‘OK, no, you’re right. I don’t need that. Next article, please.’

‘“Effects of aquatic and terrestrial habitats on the skin microbiome and growth rate of juvenile alpine newts”?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘Alpine newts sounds like a condition. I’m sorry to tell you, you’re suff ering from a terrible case of alpine newts.’

‘Can’t be worse than motion sickness,’ mumbled Charlotte, obediently peeling cling film. Then she sipped tepid bouillon and listened to the now familiar cadence of Dan’s voice, letting the words wash over her. She watched him, safe to study his face while he looked down at the pages. When he had fi nished the article, Dan set the journal down on the floor, and got to his feet. He regarded her, obviously gratified to see the mug empty in her hands.

‘Well done. I’ll head back and get organised now, I think. Do you need a hand packing up before tomorrow?’

‘No thank you.’ She handed back the cup. ‘Will there be a big crowd?’

Dan nodded, and looked, for a moment, uncharacteristically uncertain. He had paused in the doorway and now began to study the mechanism of the lock, jiggling it a little, frowning at it while he spoke.

‘Oh, you know. There’s always a crowd on Ship Day, but it’s mostly for the cargo, really; people have waited so long ship to ship. Baked beans, or a new wheelbarrow, or the next James Patterson, or whatever. A loo seat. Whisky. Flour. You cannot believe how much cake Tugans consume, for an island that isn’t wheat- producing.’

He spoke lightly but he was anxious about the landing tomorrow, Charlotte sensed, and she wondered again how it would be to return to such a small community an adult, to step straight into a senior island role, having left as a teen.

She watched him quietly from the safety of her narrow lower bunk, this man she had known for only a brief period, but one with such a strange and intimate intensity to it. Her heart went out to him. After weeks of his professional confi dence, his sudden nerves were aff ecting.

‘If you’re really feeling better, will you try and come up tonight? Watch the Island Day fireworks with me? We’ll be able to see them on deck.’ Dan released the handle, apparently satisfied.

Charlotte’s stomach turned over, and she closed her eyes. It was unfortunate that butterflies shared so many symptoms with seasickness. She opened her eyes again.

‘I might have to bring my pet bucket. Just in case.’

Dan grinned. ‘No need. There’s the whole of the South Atlantic at your disposal. See you in a bit.’ Then he was gone and Charlotte lay back.

She was young and strong, and until these last weeks had existed in the blithe ignorance of near- perfect health.

Intensely private and habitually defended, she could not help but see this motion sickness as a failure of her own self-possession. It seemed a betrayal, for where possible Charlotte avoided vulnerability, and mess. She had experienced a new alienation from the body she had always seen as herself, and was now as unreliable as everything else. It had been a year of shifting sands.

On this purgatorial sea crossing, Dr Dan Zekri had come to Charlotte as a saviour. She guessed him to be about ten years older than she was, in his late thirties, returning to his native Tuga de Oro after many years living in England. A cargo ship with only eleven passengers has no legal requirement to carry a doctor, and so it was merely good luck that a medic happened to be a fellow traveller. Dan had visited her cabin that fi rst terrible night and then every morning and evening since, with cinnarizine tablets and magical injections, with salted crackers, with blackcurrant squash, with sluice bowls, a sense of humour, and apparently unending kindness and patience.

He was also travelling alone, and had time on his hands. Unlike a passenger ship, there was nowhere on board to go, nowhere but the modest cabins to escape the roar of the engines, and the pervasive smell of stale cigarettes and diesel.

Dan talked about growing up on Tuga (the first silent bat swooping across the evening sky, he told her, was the island sign that all children had to stop playing and go home for supper, though he was unable to tell her with any satisfaction what subspecies of bat they had been). He took a medic’s interest in the fellowship that was bringing her to the island, an invitation to spend a year surveying the dwindling population of Tugan gold coin tortoises in the island’s lush, canopied interior. Charlotte, who had long ago learned that most people did not want to hear about herpetology as much as she wanted to talk about it, felt the rare pleasure of encountering someone whose intelligent enquiries made clear a genuine interest in the answers. She could speak with ease about reptiles in a way she never could about herself.

Indeed, her own escape into academia had been spurred by the realisation, at college, that domestic-animal patients necessitated a great deal of interaction with their human owners. Wildlife was owned by no one.

But Dan was an appealing human. He laughed with self-deprecation when she risked a classic veterinary joke, about doctors. (‘What do you call a vet that can only treat one animal?’) She was touched by how terrifi ed he confessed to being of cats, one of the advantages of his return home to Tuga, he declared, where there were none permitted, in order to protect the endemic bird population. He read esoteric articles aloud to her and, though he often praised their untapped power as a tranquilliser, could not help but go on to ask about reptile viral expression. He was secretly fascinated, she was sure of it.

Dan was driven, which she admired, and obsessional, which she recognised. He was full of plans for public-health initiatives on the island, additional training for the clinic’s two and a half nurses, and incentives to recruit four more. He feared he had been away too long to be accepted, but also that he had been away too long to submit himself to all the idiosyncrasies and limitations of impoverished, isolated medical practice, while acknowledging that attempted change, even for the better, would itself be a barrier to acceptance. He seemed to have the confi dence to confess his limitations.

Charlotte did not feel she could be her true self with Dan Zekri, for she could not imagine anyone would want to meet that weak and spindly person. Practised at evading intimacy, she made light of her family when he asked her questions.

She would recite her mother’s curriculum vitae – a single mother lauded at the Bar, who worked hundred- hour weeks and was devoted, with an equally meticulous focus, to the care of her daughter either directly, or by proxy. On the day she’d made silk, Lucinda had also made Charlotte a vanilla-sponge tortoise birthday cake, the scutes tessellated slices of Marks and Spencer’s chocolate Swiss roll, to be presented early the next morning before school, and court.

Over time this anecdote came to represent as much about her family as she wished to communicate, and all the right things. The story had been so often on her tongue that it was worn smooth, and snagged no further questions. To Dan she then added the frank lie that Lucinda was overjoyed about her Tugan fellowship. Charlotte wished it had been so. In fact, Lucinda herself was in Grenada for almost a month for a case, and when she eventually returned home, a note on the kitchen table confessing to this year- long relocation, five months in the planning, would be the fi rst she heard of it.

Time would tell, when her fury broke, whether the world’s most isolated island was suffi ciently far away.

It had always been hard to explain the unique constellation of circumstances that made Lucinda what she was, the central deity and infl uence in Charlotte’s life, without listeners mistaking this intensity for dysfunction. Charlotte yearned for her mother, sometimes even when she was present. Her only significant ex-boyfriend had misapprehended their dynamic, when no longer in the first fl ush of Lucinda’s concerted charm off ensive. But Lucinda had not been wrong about him, in the end. All men were unreliable, Lucinda often counselled her daughter, and he had done Charlotte a favour by revealing his fuckwittery so fast.

It was hard to talk to strangers about her father too, but for different reasons. At its worst, her ache for her mother bloomed into an ache for her father, a more diff use, pervasive sorrow for the lost, for the never- known. Fathers were anchors and bodyguards and disciplinarians; teachers and comforters; heroes or villains; fathers were embarrassments or cheerleaders or let- downs. With nothing – no name, no history – her own father was a void she could not try to comprehend, a shadow, just outside her vision. Lifelong she had believed he had not wanted her, and this rejection was all of him she had, its legacy a craving for the protective armour of emotional self- sufficiency. Charlotte looked forward to an island famously resistant to outsiders on which, she thought, no one was likely to take much interest in a quiet, self-contained herpetologist. The journey had been a torment, not to mention the confusion of her reasons for making it.

Nonetheless, ahead lay Tuga de Oro. And sitting with Dan Zekri beneath a tropical sky alight with fireworks was not a bad way to begin an adventure.

To read more, buy a copy of Welcome To Glorious Tuga by Francesca Segal, out now in paperback...