For the first half of my life, I genuinely believed I was stupid. I didn't know I was dyslexic, didn't know I had ADHD. What I did know was that I couldn't keep up. I couldn't spell or read or do my times tables like the other children. When you're a child and the world doesn't understand you, you begin to think the problem must be you.

Even now, people think you're lazy, difficult or disruptive – there's still so much stigma and so much shame that surrounds dyslexia but as the saying goes: if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it'll always feel like a failure.

Back in the 1980s, dyslexia wasn't something schools really looked for or recognised. If you struggled, you were lazy and if you didn't get it you were stupid. When those labels are thrown at you day after day they start to stick. Parents tend to believe what teachers tell them and when everyone in your life starts to see you in a certain way, you believe them too. Eventually, I stopped going to school. Bunking off was easier than facing the dread of another test I knew I'd fail.

What to read next

The system didn't ask why, and I believed that I deserved it so I became a truant – and then a thief. I didn't want to be bad but I was so angry – so frustrated – with myself, I couldn't make sense of why everything seemed harder for me than it was for everyone else.

After school, I found work in a sewing factory. It was a start – there was a wage and a routine, but it wasn't fulfilling. I wanted to do more and be more but I couldn't find another door in.

And then, in adulthood, came the diagnosis.

It was like finding the missing piece of the puzzle I didn't know I'd been building my whole life. It finally clicked into place. All the confusion, all the shame, the self-doubt – they all made sense, suddenly. I wasn't stupid. I was dyslexic. It changed everything.

Since then, I've spent the next twenty years unravelling the first thirty. After the diagnosis it was like a complete reset. I now hold several fellowships and I'm chartered; as a Head of Sustainability and a Climate Commissioner I chair a global employee resource group; am up for an award – Environmental Professional of the Year – and I've even spoken at the United Nations. That was completely unthinkable when I was working at the factory all those years ago.

It doesn't mean that the imposter syndrome doesn't creep its way back in though. That feeling that one day someone will tap me on the shoulder and remind me I don't belong here. That's the power of stigma.

Just like Jamie Oliver discussed in his documentary, there are still too many people who are made to feel ashamed of how their brains work. Too many hide their diagnosis, terrified of being seen as less capable. I did too, for a long time. A friend urged me to speak up but I was so terrified I would lose everything that I kept my dyslexia hidden for a long time.

The workplace hasn’t always felt the safest space for someone like me. Most are built on rigid processes and neat boxes – things that don’t fit the way my brain works. But I’ve come to understand that my creativity, my ability to think differently, is a skill, not a shortcoming. And that’s something employers are only just beginning to realise, too.

We don’t celebrate disability. We should, but we don’t. And yet, understanding mine has given me back my education – and, in many ways, my life. Now, I want to use that knowledge to help others like me.

The most powerful thing an employer can do? Create a safe space. Make it clear that dyslexia – thinking differently – isn't something to be fixed but to be valued.

It's funny because tools like AI have completely changed the game. I've named mine Betty – a good Yorkshire name – and she helps me when the words don't come, when the sentences tangle. I just type everything I'm trying to say into the AI and Betty untangles what I mean. She helps to level the playing field and when used responsibly, she's a gift.

How to spot the signs?

Dyslexia can wear many masks – especially for women, who are experts at masking when they're struggling – but there are tell tale signs. Of course there's the difficulty with spelling or with maths problems but it can also look like a child who is disruptive or distracted. Sometimes it could be a quiet one who's always tired. The girl doing her homework every night but getting poor marks because the ideas in her head just won't come out the way school wants them to.

It can look like frustration. Like acting out. It can even look like toilet troubles in young children – bed wetting is a common sign but I didn't know that until much much later.

There's a domino effect, too. Poor grades and struggling at school can lead to low self-worth, anxiety and then to acting out – people are all too willing to write you off, never realising there's a real, capable person underneath.

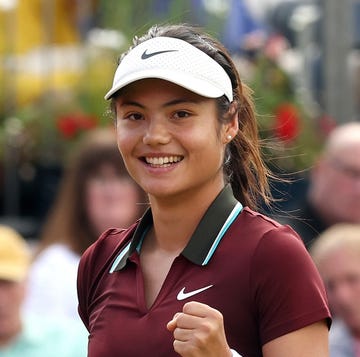

And people like Jamie Oliver, who’ve spoken openly about their own neurodivergence, are helping change the narrative. I just wish I’d heard those stories sooner.

Because here’s the truth: I always knew I was capable. I just needed someone to understand how I was capable.

And now, I want to be that person for all those children who are struggling like I did.