On 6 May, the eyes of the world will be on Westminster Abbey when King Charles III is crowned alongside Camilla, The Queen Consort. It will be a truly historic moment: the first coronation that most people will remember. As the day draws closer, speculation is reaching fever pitch about what it will be like.

Buckingham Palace has said that the event will be "rooted in long-standing traditions and pageantry." And there are certainly plenty of those to draw on. Coronations have been the high point of British royal pomp and pageantry for well over 1,000 years. These glittering occasions celebrate a new reign and also symbolise the monarch’s headship of the state and church.

Although there has been incredible change over the centuries, the crowning of a new king or queen has remained surprisingly constant. The ceremony followed at Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 was almost exactly the same as that used for King Edgar in 973. It begins with the new monarch being presented to the congregation by the presiding cleric (who since 1154 has always been the Archbishop of Canterbury). Next comes the oath, when the monarch swears to uphold the law and the church. The most sacred part of the ceremony follows, when the sovereign is anointed with holy oil. Finally, they are invested with the royal insignia (robe, ring, orb, sceptre) and crowned.

Other aspects of this ancient service have changed little over the centuries. Handel’s rousing anthem Zadok The Priest, which he composed for George II’s coronation in 1727, has been played at every coronation since. The dazzling Gold State Coach, first built for George III in 1762 and used at every coronation since that of his son, George IV, will carry The King and Queen Consort to Westminster Abbey. The coach might be lavish but it’s not all that practical. Measuring seven metres in length and weighing in at four tonnes, it takes eight horses to draw it and can only ever go at walking pace. On the day of Elizabeth II’s coronation, Royal Mews staff strapped a hot water bottle under the seat because it was so chilly.

Two crowns for the King

The Crown Jewels are, of course, an essential part of the coronation. King Charles III will be crowned with St Edward’s Crown, as per tradition. The crown was made for Charles II in 1661, who commissioned a new set of Crown Jewels to replace those melted down after the execution of his father, Charles I, in 1649. Inspired by the crown of the 11th-century king, Edward the Confessor, St Edward’s Crown is made up of a solid gold frame set with rubies, sapphires and other precious stones. St Edward’s Crown is only ever used for the crowning itself. It is swapped at the end for the no less dazzling Imperial State Crown, which was made for the coronation of George VI, in 1937. There are reasons of practicality for changing to the Imperial State Crown for the procession – as it is lighter and

more comfortable.

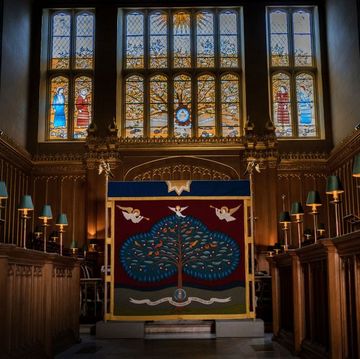

The Queen Consort will wear a crown that was made in 1911 for Queen Mary, the wife of George V. It is the first time in recent history that a new crown has not been commissioned for a Queen Consort. However, the crown is undergoing modification for the occasion – it is being reset with diamonds that were part of the private collection of Queen Elizabeth ll. In choosing Westminster Abbey, King Charles is upholding almost 1,000 years of tradition. Founded by Edward the Confessor, it has been the setting for every coronation since 1066, as well as for numerous other royal occasions such as – in recent times – the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton in 2011 and the state funeral of our late Queen last year.

The Abbey houses the Coronation Chair, which has been the centrepiece of coronations for more than 700 years. It was originally made on the order of King Edward I, the so-called "Hammer of the Scots." He had it designed to enclose the ancient Stone of Scone (also known as the Stone of Destiny), which had been used at the coronations of Scottish kings but which Edward took back to England when he invaded the country in 1296. The stone remained within the Coronation Chair until 1950, when a group of enterprising Scottish students stole it from Westminster Abbey and returned it to Scotland. After some delicate negotiations, it was brought back to London in time for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and it will return again for that of her son.

A cloth of gold

The planning of a coronation runs like a well-oiled machine. The Earl Marshal has overall responsibility for the proceedings; a position that has been given to the Dukes of Norfolk since 1672. The current Duke is Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, who will be assisted by government ministers, the royal household, the Church of England and the Commonwealth realms.

The late Queen’s coronation might provide a useful model for the planning. Held on an unseasonably cold, wet June day in 1953, it was probably the most meticulously prepared-for coronation in history. The Earl Marshal had drawn up no fewer than 94 diagrams, "each depicting different parts of the ceremony in which every minute was worked out, and every movement within each minute prescribed," as one of Elizabeth II’s attendants later recalled.

There were certainly a lot of minutes to plan. The Queen and her ladies were woken at 5am to be dressed and made ready, and the guests began taking their seats at 7am, even though the ceremony did not begin for another four hours. A staggering 8,251 guests were crammed into the Abbey for the occasion – more than four times as many as attended her state funeral. A further 20m people across the country were able to watch the ceremony, thanks to the fact that it was the first coronation to be televised. This had been the idea of Prince Philip, who had encountered considerable opposition among the royal household. But he had his wife’s support and a compromise was reached whereby only for the most sacred part of the ceremony – the anointing and communion – were the cameras turned off.

The ceremony lasted for two and a half hours, towards the end of which the Queen and her ladies were beginning to flag – one of them had almost fainted during the anointing. But help was at hand as Elizabeth entered St Edward’s Chapel to change crowns and also her robe for the final procession. For the moment of crowning, the monarch is invested with robes known as the "Colobium Sindonis" and the "Supertunica," or cloth of gold. They then remove these during the recess and proceed out of the Abbey in the same clothes they wore to come in. The Archbishop of Canterbury handed round a flask of brandy. The Queen and her party then tucked into some sausage rolls, smoked salmon, and cheese and biscuits before re-emerging for the last half an hour of the service, with not a biscuit crumb in sight!

In tune with the times

The scale of Elizabeth II’s coronation served a very deliberate purpose. As well as celebrating the dawn of a new reign, it also put Britain on the map in the years after the Second World War. The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, reflected that the coronation had strengthened the link between the crown and the nation’s identity. It also gave the country something to smile about at a time of economic hardship, with post-war rationing still in place.

Other coronations have been similarly in tune with the times. When the late Queen’s father, Bertie, became King in 1936 after the abdication of his brother Edward VIII, he admitted that he had inherited "a rocking throne" and tried "to make it steady again." His first step was to take the name of George VI to emphasise the continuity with the reign of his popular father, George V. He was crowned on the day that his elder brother should have been (12 May 1937) and privately admitted to "a sinking feeling" when he awoke that morning. In accordance with his wishes, the procession was broadcast to a worldwide audience, although the service itself remained the private religious ceremony that this intensely pious monarch believed it should be. Putting the morality back into the monarchy was just what was required after the antics of George VI’s brother and Wallis Simpson.

King Charles’s coronation is also expected to be in tune with the times. Buckingham Palace has said that it will "reflect the Monarch’s role today and look towards the future." Held in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, it is likely to be on a significantly smaller scale than his mother’s. The chances are that it will also reflect the vastly different times in which we live compared to 70 years ago. In his first speech as King, Charles referred to a "fearless embrace of progress" and reflected that British society had "become one of many cultures and many faiths."

That said, we can still expect plenty of the centuries-old pomp and pageantry that makes British royal events the envy of the world. As a politician during Queen Victoria’s reign put it: "The mass of people expect a King or Queen to look and play the part. They want to see a crown and sceptre and all that sort of thing. They want the gilding for their money." So, sit back, relax and prepare to be dazzled on the day.

Tracy Borman is joint chief curator at Historic Royal Palaces. Her first theatre tour, How To Be A Good Monarch, began on 17 April. Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I: The Mother And Daughter Who Changed History (Hodder & Stoughton) by Tracy Borman is out on 18 May.