“Should I go out with him?” I sent my friend group a screenshot featuring the Tinder profile of a dark-haired man in a dress shirt. His brief check-ins, more like properly punctuated reminders from a dentist’s office than flirty texts, were hardly the rambling epistolary affairs I’d received before. In fact, I told my friends, he’d sent me a total of one short — albeit pleasant — paragraph over a week, and now he was asking to meet.

“Too soon,” one friend wrote.

“Bad texter means a bad date,” said a second.

“Give it another week,” said the third. “See if he opens up.”

I didn’t know if either of us were interested enough to last another week. His invitation had read simply: Do you want to go out sometime?

Online, we have to take each other’s word for it.

In the world of online dating, writing is all we have, at least at first. You’d think, as a novelist, I would have been better at using the tools of my trade to forge a genuine connection that resulted in true love. Many times, I thought I had.

There was the up-and-coming chef who would playfully volley with me via text about everything from the Beatles to the futility of existence until the wee hours of the morning. I love your mind, he wrote in one message. I love yours, I wrote back. We’d only been texting for a few days, but it felt real.

Then there was the attorney whose dark humor made me snort-laugh on breaks between client meetings. He would send me YouTube videos with his commentary or captioned pictures of his two Yorkies. He once wrote in a “goodnight” text that I gave him butterflies —no, more like pterodactyls, he corrected — which made me blush.

What can I say? I’m a sucker for words. I felt I was using online dating to its fullest potential, reaching people who I would never encounter otherwise, both of us lighting up our screens with greetings that became jokes, and then jokes that became inside jokes, notification by notification, writing the story of our budding relationship.

But the thing about stories is sometimes they aren’t true.

In the "real world," words can fail.

One day out of the blue, the attorney sent me his usual midday message, but this time he wrote to break up. You want more than I can give you, he said. How do you know what I want? I asked. Our messages, he said. He had inferred.

Months before that, the chef had stopped responding to calls and texts. When he finally got back to me, he apologized, told me he’d been “taking a lot of mushrooms lately,” and brought me to a state park, where he pulled out a machete and began to hack at the prairie grass, insisting we find a good place for his “snapping turtle traps.” Magic mushrooms, sharp objects and illegal traps on state land: not a good combination. This man was clearly going through something, and soon I learned that our little blue bubbles, rather than being the beginning of a life he wanted to share, were supposed to be an escape. I admit I did try the snapping turtle stew he eventually made, which was delicious, but we ate in silence. No more late-night brainstorms.

And the musician who sent me adorable videos of himself dancing to Prince in the old farmhouse he was restoring? He began to mention his ex-wife. A lot. Then, the English teacher who waxed poetic on books avoided meeting offline for months, until it was revealed his “open marriage” was more closed than he had let on.

All of these men and me; we weren’t falling for each other, we were falling for the power of words. We were using the exchange of tiny love letters to play pretend, with each other and with ourselves.

Now, the bad texter’s invitation waited in my inbox. There was a chance his brevity could be a sign that he wasn’t worth the bother. But there was also something refreshingly confident about it. He didn’t want to write, he wanted to meet, and no matter how long we played phone tag, the only chance for real connection was being vulnerable, being present, being ready to love.

I could certainly use online dating to message with a stranger about these things, but in order to really do them, and in order to know whether the stranger I’ve chosen is ready to do them, too, maybe I would simply have to show up.

Finally, we had our meet-cute.

It was a breakfast date. At the coffee shop counter, we waved awkwardly at each other behind our masks. Outside, we took them off. I apologized for spilling scone crumbs all over our table — usually I came here alone to work on edits, I told him. He drank orange juice and answered all my questions about what it was like to be on local TV. (He’d been recognized once or twice in the grocery store, but that was about it).

After a while, I asked him what he liked to do outside of his job. “Actually, same as you,” he said, gesturing toward me. “I love to write.”

I found myself smiling, first with irony, and then genuinely. “Oh, really?” I said. “I wouldn’t have guessed.”

Two years later, we’re about to get married. Not everyone I met was worth going offline for, but the immediate attraction and safety I felt in his presence was better than any sweet nothing I could have gotten in my inbox.

Sometimes love stories can’t be written. They have to be lived.

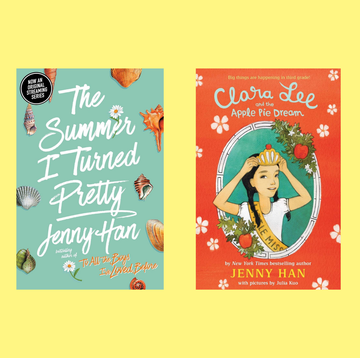

Lara Avery's newest book, The Year of Second Chances, is now available at your favorite bookseller. This essay is part of a series highlighting the Good Housekeeping Book Club — you can join the conversation and check out more of our favorite book recommendations.

Lara Avery is the author of The Year of Second Chances, three young adult novels and her articles and essays appear in San Francisco Chronicle, Gay Mag, Pollen, ARTNews and Women In Clothes. She lives in Topeka, KS with her husband.