“Did you know that Rebecca moved back to town?” my mom asked over lunch. My mom explained that she and her husband Dave wanted to be closer to their parents and to Dave’s siblings. She’d heard all this from Rebecca’s parents, who’d been her friends since the early 1970s.

It was the last thing I’d expected of her. My childhood friend Rebecca had lived in Manhattan since moving for grad school in her twenties. She worked for an art gallery, and her husband was a TV producer. They didn't have kids, and though we hadn’t talked in more than 10 years, I’d always pictured them living quintessential New York lives. I couldn’t fathom why they’d want to move back to our hometown in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, where we’d spent our teen years lamenting the fact that there was absolutely nothing to do.

Rebecca and I hadn’t gone to the same schools, but we’d seen each other so often, at barbecues, birthday parties and most notably a series of epic family New Years’ Eve parties, that she sometimes seemed more like a cousin than a friend — someone who was part of me in a way that circumvented choice and affinity.

“You should call her,” my mom said, and I said okay, even though I knew I never would. Too much had happened.

Ours was the kind of friendship that feels like family

My mom brought over a photo album to show my husband, a tour of who I'd been before we got together. As we looked through it, I pointed out the pictures of Rebecca, whom he’d never met. Here we are at my fourth birthday party, at a McDonald’s that's now a Japanese restaurant. Here we are at my eighth birthday party, posing in oversize T-shirts and masks that my stepdad brought home from the local opera company where he volunteered backstage.

He’d already seen the one of me with Rebecca in Paris during our junior year abroad. It’s a close-up in some indeterminate location, both of us blurry and vague. On the next page was one of my twenty-fifth birthday party at a bar in D.C., both of us in sundresses, long hair loose down our backs. “You always look like you’re having so much fun,” my husband said.

“We were,” I said. “We did.” I told him about the time Rebecca came over for New Year’s Eve and we mixed Diet Coke with a Greek liquor called ouzo and then crawled out on the roof outside my bedroom window to smoke, somehow managing not to topple off on to the driveway. I told him about the weekend we’d spent in London, where we met three boys who squired us around town all night before we finally ended up at an after-hours called The Church in the early hours of Sunday morning. No one paired off or hooked up; Rebecca had a boyfriend back home, and anyway that wasn’t the point. We were there not for love or drama but simply to have fun, because that was what Rebecca was all about.

Rebecca had the best comic timing of anyone I’d ever known, a way of drawling out a single word or phrase that would have me in hysterics. She and Dave were like a comedy duo, batting an idea back and forth while I snorted with laughter. When they moved to New York in 2006, I visited them a time or two, and she came to see me when I lived in D.C. and in coastal South Carolina, where I spent a glum month in a rented condo trying to write my first book. She was in my first wedding, one of three bridesmaids; I was in her wedding, also one of three. It never even occurred to me that there might be a time when she wasn’t in my life.

I felt lucky to be in her orbit, until I wasn't

But then, when we were in our early thirties, something changed. When we were both home for the holidays, I called her as usual to make plans, but she didn’t call back. I tried again — first text, and then email — but she never replied. I didn’t hear from her when my first child was born or when my first book came out, and I didn’t contact her when I heard she had a great new job at a Chelsea gallery. I let the time when I could have reached out to ask for an explanation expire, until it got to the point where even thinking about picking up the phone felt strange.

Besides, I was already pretty sure what had happened. Rebecca had finally figured out that she was way too cool to be my friend. She’d always been funnier and more popular, and now, when she was living it up in New York and I was in the hinterlands of the Midwest with a baby and a mortgage, the gulf between us had become too wide. My mind kept coming back to a story my first husband had told me about a night when the three of us were out and I’d gone to the bathroom, prompting Rebecca to lean across the table and say, “Polly isn’t fun anymore. We used to dance on tables, and now she’s in bed by nine o’clock!”

We had never actually danced on a table, but the phrase had become our private shorthand for squeezing the maximum amount of fun out of any particular night. Rebecca had given me permission to be a different version of myself — more relaxed, more confident, perhaps a bit more reckless. Now I was growing out of that phase, and she must have concluded that we no longer had anything in common.

Rebecca had always been good at telling it straight. Once she’d ended a date in the middle of dinner, telling the guy, “Sorry, I don’t think this is going to work.” Shortly after college, she’d broken up with another one because he served her jarred pasta sauce. She was unapologetic about her lack of patience with things and people that bored her, and that was one of the things I’d loved about her. Until I felt like I’d become one of them.

When it came to endings, I was the opposite of Rebecca, prone to hang on long after a relationship had passed its sell-by date. I went to great lengths to stay on good terms with all my exes, wishing them happy birthday and exchanging the occasional catch-up email even with the ones I’d never liked much in the first place. Rebecca had showed me that even the longest, most permanent-seeming relationship could outlive its usefulness, and that was a gift no matter how much it hurt.

“But what if you’re wrong?” my husband asked. “What if she’s actually not mad at you or whatever? What if she just forgot to call you back and then things got awkward?”

Maybe it wasn’t about me, after all

I had to admit he had a point. Like most people, I’m prone to interpreting everything that happens in my general vicinity in the most egocentric way. It was possible that I’d fabricated this narrative about Rebecca discarding me on charges of unhipness and she’d be happy to hear from me. Before I could change my mind, I opened an email and typed out a message, congratulating her on the new job and asking if she wanted to get together.

Six days went by—long enough that I told myself that I’d been right the first time. Then a message popped up: Hi Polly, it’s so nice to hear from you! She talked a little bit about her job and moving home before ending with, I’ll text you so we can organize a get-together. Can’t wait to catch up!

We made plans to meet for drinks the following week. In a flash, I could see how wrong I had been. For the past 10 years, while I’d been having children and writing books, getting a Ph.D. and getting divorced and remarried, Rebecca had been living her own life that had nothing to do with me. She’d been busy, successful and certainly not spending her time looking down on me for making different life choices. We were in our forties now, two middle-aged women with aging parents and demanding careers — who has time for that?

Should we dance on the tables? I wrote. I didn’t know if she’d get the reference. It had been so long. We had missed so much. But it was only a few minutes before she wrote back. Always, she wrote with a wink.

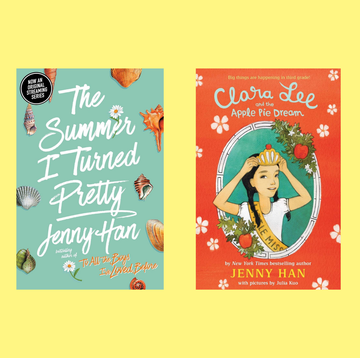

Polly Stewart's debut thriller The Good Ones is out now from your favorite bookseller. This essay is part of a series highlighting the Good Housekeeping Book Club — you can join the conversation and check out more of our favorite book recommendations.

Polly Stewart was born and raised in the Blue Ridge, where she still lives. Her short fiction has appeared in Best New American Voices and Best American Mystery Stories, and in Epoch, Alaska Quarterly Review, as well as other journals. She writes a new monthly interview column for Crime Reads called The Backlist, and her nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times and Poets & Writers, among other publications. Her debut thriller THE GOOD ONES is out now. For more on Polly, visit: www.pollystewart.com.